Posted: April 20, 2022

Altering the mix of foods and drinks available in shops, restaurants and bars could help improve diets, reduce inequalities and protect the environment, according to a new analysis by Professor Theresa Marteau and colleagues at the Universities of Cambridge, UCL, Oxford and Aston.

Such measures, called availability interventions, might see a proportion of confectionery items on offer in supermarkets replaced with fruit or nuts, for example; or some meat based meals replaced with plant-based ones on a restaurant menu.

Unhealthy diets are one of the largest contributors to preventable disease, health inequalities and early deaths worldwide. Policies and interventions that reduce the supply and consumption of meat, alcohol and sugary foods would improve population health globally, reduce health inequalities and help limit environmental harms associated with food production.

Professor Marteau and colleagues, writing in the BMJ, explain that to make a substantial difference, a range of interventions is needed, that reach everyone, without increasing health inequalities.

The team highlight the potential of availability interventions to contribute to population health and net zero goals, alongside measures such as higher taxes and marketing restrictions on unhealthier products. Yet availability interventions remain largely overlooked by policy makers.

The team set out to summarise the evidence supporting availability interventions in a form useful to policy makers. They searched the scientific literature to update a Cochrane review published in 2019 and identified nine real world studies, including four new ones.

The new analysis shows that availability interventions deliver consistent and often substantial effects on consumer selection of healthier or more sustainable options. Even though the studies were carried out in different settings, exploring the effects of different interventions, together they show that reducing the proportion of a target subset of food or drink reduces its selection by consumers, often markedly so.

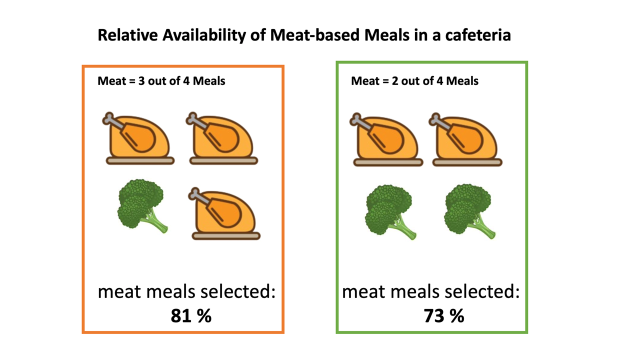

For example, increasing the proportion of vegetarian meal options in a cafeteria from 25% to 50% decreased the selection of meat meals by almost eight percentage points (from 81% to 73%).

Similarly, increasing the proportion of lower energy food options available in cafeterias from 42% to 50% reduced the calories purchased per transaction by almost five percent compared with baseline (from 384 to 366 kcal).

And early results from a study of online supermarket purchases suggest that decreasing the proportion of alcoholic drinks available from 75% to 50% and 25% increased the proportion of non-alcoholic beers and wines and soft drinks selected from 24% to 32% and 45% respectively.

The authors acknowledge some uncertainties, such as whether these findings can be applied to low and middle income countries, and the impact of population preferences and social norms on what we eat.

And they point to challenges that they say may contribute to the relative neglect of these interventions. They don’t fit the dominant public discourse around personal responsibility for unhealthy behaviour, and they may be resisted by businesses fearing loss of sales.

Nevertheless, they say their findings should help highlight the opportunities for including availability interventions in strategies promoting health and sustainability.

Professor Marteau, lead author, said: “Evidence for the effectiveness of availability interventions is now mature enough to merit serious consideration by policy makers and others as an effective addition to interventions in public and private sector settings aiming to shift currently unhealthy and unsustainable patterns of consumption towards unmet population health and net zero goals.”